The Lake Washington/Cedar/Sammamish Watershed is proof that even in the most populated watershed in the state, salmon are still surviving. Every year salmon spawn and rear in this watershed rivers and streams, and use the lakes, river, estuary, and nearshore to rear and migrate to the ocean.

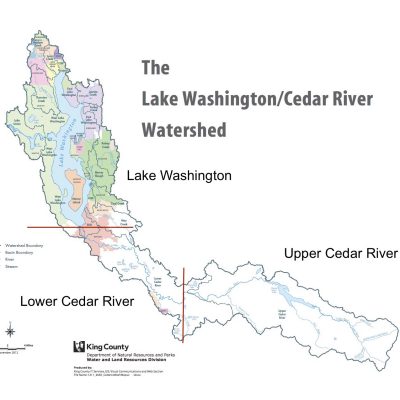

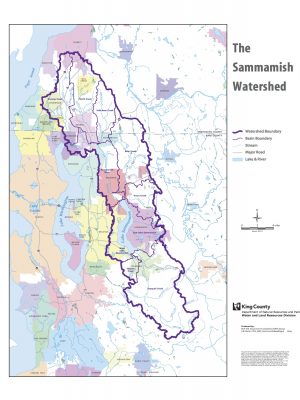

At the largest level, a watershed is defined by its geography – the rivers and lakes of which it is comprised. This watershed has two main sub-watersheds that come together: The Cedar River-Lake Washington Watershed and The Sammamish Watershed.

Each of those sub-basins has its own historic populations of fish, whose populations are each impacted by the changes in the rivers and streams of the watersheds.

The bulk of the area of this watershed is the Cedar River watershed. The Cedar River originates in the Cascade Mountains then flows into the southern shore of Lake Washington and out through the Hiram Chittenden Locks (Ballard Lock). The river length is about 46 miles and can be separated into the upper Cedar River, above Landsburg Dam, and the lower Cedar River. The upper Cedar River is mostly forested , and is the source for drinking water for the City of Seattle. The Lower Cedar River has a wide floodplain in many areas and many tributaries. This area contains a mixture of land use, and still has some good forest cover. However, rapidly expanding urbanization has occurred in the vicinity of Renton and Maple Valley. The Cedar River is home to Chinook salmon, sockeye, coho, steelhead and trout

Lake Washington receives inflow from the Cedar and Sammamish Rivers, as well as numerous smaller creeks. The lake drains through the Ship Canal then out through the Ballard Locks to Puget Sound. The most of the lake shoreline surround with the residential and commercial uses.

The Sammamish Watershed encompasses 240 square miles. Numerous creeks feed Lake Sammamish, with Issaquah Creek being the largest. Then, the Sammamish River carries water from Lake Sammamish to Lake Washington.

Lake Sammamish covers about 7.6 square miles which Issaquah Creek is the major tributary to Lake Sammamish. Tibbets Creek to the south, and Pine Lake Creek to the east, also drain into Lake Sammamish. The majority of the lake shoreline is privately owned.

The Sammamish River has 13.8 miles in length, connecting the northern ends of lakes Sammamish and Washington. The river can be divided into two sections based on topography. The upstream section, running from the outlet at Lake Sammamish to River Mile 4.5 (where North Creek discharges to Sammamish River), runs through a broad valley including open space and recreation, urban residential and commercial uses, and agriculture. The lower section, from the River Mile 4.5 to the confluence of Lake Washington, has a narrower valley. Land use similar to upper section, include urban development and open space.

The Sammamish Watershed is home to Chinook, coho, sockeye, kokanee, steelhead, and coastal cutthroat. In addition, it is home to one of only 2 native populations of Kokanee salmon, a form of land-locked sockeye, in Washington state.

Challenges of History, Development and Population

The Lake Washington/Cedar/Sammamish watershed has undergone some drastic changes as the region’s economy has developed.

The rivers have been straightened and diked, to protect surrounding areas from flooding, and to make them more passable. This process disconnects the river from important floodplain areas, where complex habitat with wetland areas, pools, and wood are important rearing areas for young salmon.

These diked and developed streams also often lack native trees and plants. This has resulted in water that is often too hot for fish at key times of the year – like in the early fall when salmon are returning to spawn. The lack of trees also means that there is too little wood in the water itself. This wood can create pools and hiding places for young fish, as well as providing an abundant source of bugs and other food.

Increased development also has resulted in a change in how water enters the river during storms. In the past, natural forested areas caught the rainwater, and slowed its progress toward the nearest stream or river. The soil also cleaned any impurities along the way. With increased roads, houses, and driveways, water now flows faster into the river – creating higher, faster flows that can scour the streams and increase erosion. The rainwater also picks up oil, chemicals and bacteria on its way, so that it decreases water quality in the streams.

Development has also blocked fish access to many streams, as roads were built in such a way that the water could pass under, but the fish couldn’t get back up.

One development project that has impacted all of the anadromous fish (fish that travel from the salt-water Sound to the fresh-water rivers) was the construction of the Ballard Locks. The Ballard Locks were constructed in 1911 to allow for boats to come in and out of the watershed. The creation of the locks expanded development opportunities for the growing region, but also created ecological challenges. Migrating salmon must now make a treacherous journey through the antiquated structure to both enter and exit the watershed.

Communities Restoring Habitat

As communities have noticed the decline in the numbers of salmon returning, they have set about trying to restore the habitat, in ways that will have the biggest impact.

The Cedar/Lake Washington/Sammamish watershed group has identified the top priorities for restoration, and is helping coordinate many partners to develop and fund projects. Mid Sound is proud to be engaged in this community effort.

The below projects show just a few of the inspiring examples of restoration projects in the watershed.

Project

- Fish Passage at Landsburg Dam: The uppermost areas of the Cedar River watershed are protected and managed by the City of Seattle for drinking water which the Landsburg Diversion Dam, which was constructed in 1901 without the ability for fish to pass upstream of the dam. In 2003, the City of Seattle restored fish passage at Landsburg, allowing access to approximately 17 miles of protected habitat for spawning and rearing.

A tip-out downstream passage gate at the diversion dam to provide safe passage for downstream migrating fish as they pass – Landsburg Dam

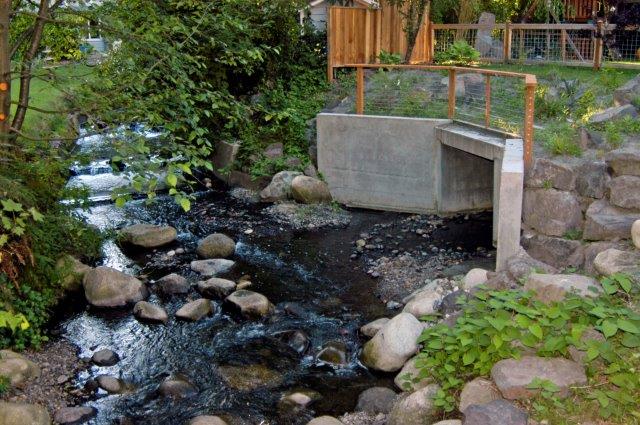

- Little Brook Creek: This project replaced undersized culvert to a box culvert, the old culvert also was perched 12 inches above the water, the constrictive culvert created a full blockage to the entire creek. Fish passage was impossible. Little Brook Creek is a tributary to Thornton Creek, it runs mostly through the backyards of a residential neighborhood, and is home to Coho and Chinook salmon, as well as Rainbow and Cutthroat trout. In addition, in-stream habitat features were installed both upstream and downstream of the new box culvert.

The old, 2 foot culvert that blocked the fish

The entryway of the new and improved culvert

which is now approximately 6 feet wide and 7 feet tall

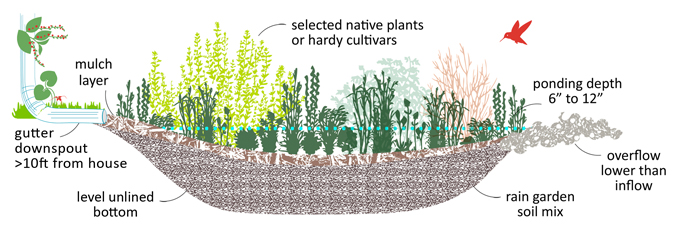

- Rain Garden: Washington State University and Stewardship Partners are leading a groundbreaking campaign to install rain gardens in the Seattle/Puget Sound Region. A rain garden is a bowl-shaped garden designed to capture and filter stormwater runoff from roofs, driveways and other hard surfaces, keeping it from becoming harmful water pollution. Many Puget Sound area schools have already installed rain gardens including Wedgwood Elementary, BF Day Elementary, Yelm High School, Mercer Island High School and more. Handbook for Homeowners Click!

Happy students at Wedgewood Elementary

Rain Garden Cross Section

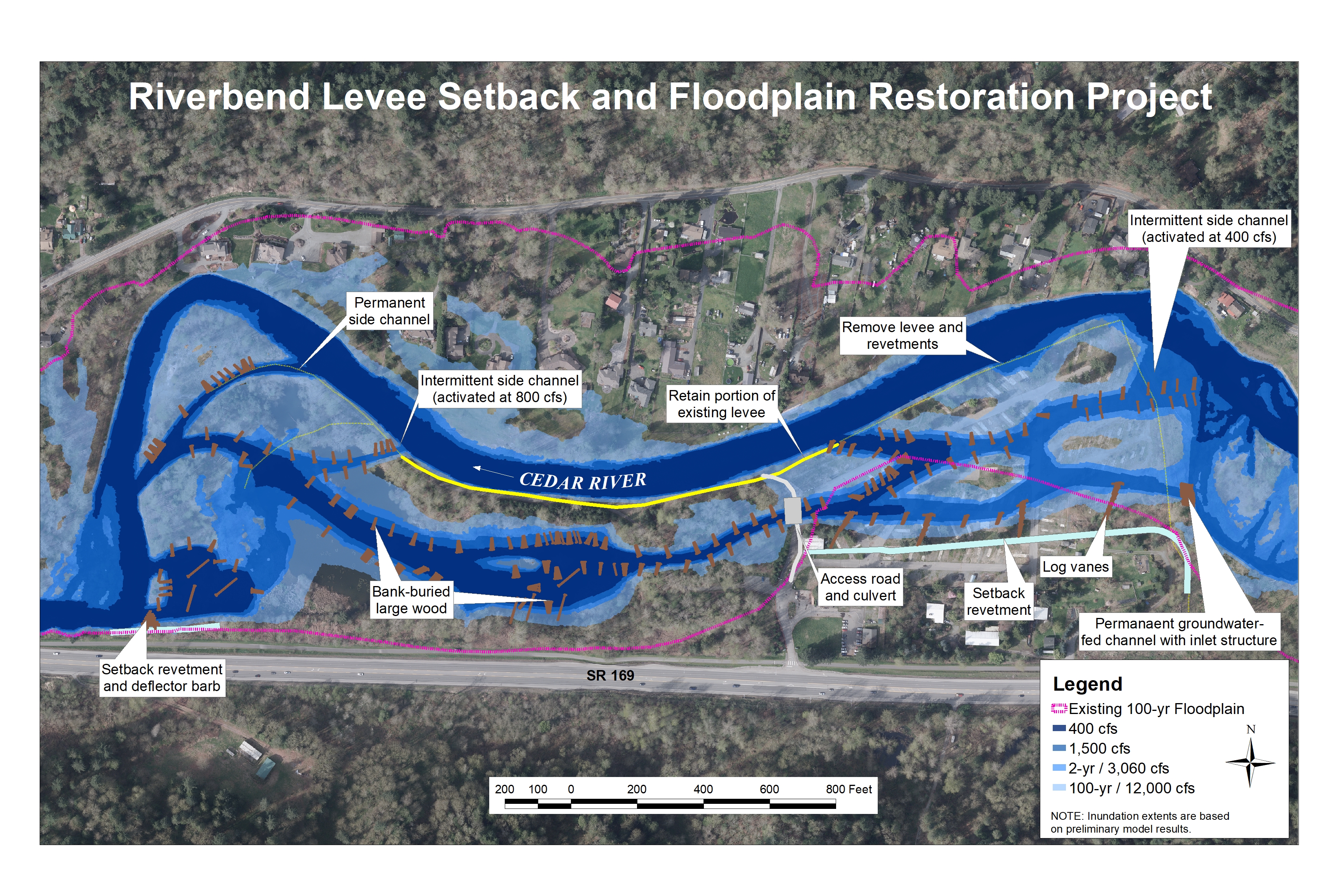

- Restoring Floodplain Habitat Along the Cedar River: Cedar River floodplain habitat is important areas for juvenile salmon to feed and grow as they migrate to the ocean. These areas also provide excellent spawning habitat. Restoring floodplain habitat at Rainbow Bend on the Cedar River is the biggest salmon habitat restoration project done to date on the Cedar River. Following the purchase and removal of a 50-unit mobile home park and ten single-family homes, a 900-foot levee and other bank armoring were removed, which reconnected the river and fish to over 40 acres of floodplain habitat. In addition to restoring critical habitat, the project eliminated chronic residential flooding. (www.kingcounty.gov)

Project Site Before

After Acquisition, Relocation, and Construction

- Sammamish River Revegetation: The Sammamish river experiences high water temperatures and low oxygen levels—both of which are a serious threat to the Sammamish population of Chinook salmon. Planting more trees along the banks of the river could shade and cool the river. Now Mid Sound Fisheries Enhancement Group is working with King County Parks and volunteers to remove the invasive blackberries on an 800 foot stretch of the Sammamish River by the former Redhook Brewery site.

Sammamish River cover with blackberry

Fish of the Watershed

There are a number of species of salmonids in the watershed, including two populations of the endangered Chinook salmon, one spawning in the Cedar and one in the Sammamish basin. Cities and communities have come together to restore these fish through the Cedar/Lake Washington/Sammamish WRIA 8 Salmon Recovery Council. This group works to prioritize and find funding for important habitat restoration, education, and water quality projects.

A male (background) and female (foreground) Kokanee salmon pair up to spawn in Ebright Creek, photo by Roger Tabor, USFWS

A male (background) and female (foreground) Kokanee salmon pair up to spawn in Ebright Creek, photo by Roger Tabor, USFWS

The watershed is also home to a beloved population of resident sockeye salmon, the Lake Sammamish Kokanee salmon. These fish were once the main type of salmon in the watershed, and were a major food source for the Snoqualmie Tribe. Now, however, returns are often now only several hundred fish.

This land-locked salmon live most of their lives in the lake, never venturing to saltwater. When it is time to spawn (reproduce) they travel up the steams of Lake Sammamish to spawn. It is thought that one run is extinct, and the remaining populations only spawn in three remaining streams.

The Lake Sammamish Kokanee Work Group, a group of governments and citizens dedicated to protecting the fish, are working to restore spawning habitat and water quality while using an emergency hatchery program to keep them from going extinct.

This visual article does a good job of telling the story of the fish, and efforts to educate future generations about how to save them.

Other types of salmon in the watershed include Coho, Sockeye, Steelhead, Bull Trout, and Cutthroat.

Challenges to Fish

This watershed is the most populated watershed in the Puget Sound, with nearly 1.4 million people living in the 26 cities and rural areas. As a result, much of the habitat has been modified. Barriers now block streams. Side channels that once provided refuge during floods have been filled. Rapid erosion has silted up spawning gravel beds. Wetlands, lake shores, and saltwater areas have been filled and barred by bulkheads.

Salmon also need clean, cool water to survive. The trees that once kept the water cool have been cut down. Pollution from cars, industry, and everyday life contaminate the water.

But people like you and I can help — either by building restoration project, or taking actions in our own life to clean water and help fish.

Mid Sound’s Work

Mid Sound has been working on several habitat projects with the Kokanee Work Group, including Ebright Creek and Lewis Creek.

We have also worked with landowners throughout the watershed, such as on the Little Brook Creek project and the Kelsey Creek project.

In the saltwater portion of the habitat, we have worked to monitor Forage Fish at Carkeek Park.

How you can help

Do you live in the watershed? Check out our What You Can Do page for more tips on actions you can take to help salmon whether you live on a stream, a lake, a beach or elsewhere in the watershed.

You can see fish in the streams in fall each year. The Salmon SEEson program has a list of great viewing sites.