Well-Designed Shoreline Armor Removal

Why Remove These Historic Structures Now?

The Kitsap County Shoreline is a small thread in the great web – the system spanning the 1200 mile migration a salmon spotted in our waters might cover in a lifetime. Regional Fisheries Enhancement Groups (RFEGs) are working throughout the system to effect the change we can:

Engage in habitat restoration that reconnect rivers to their floodplains

Remove fish passage barriers where creeks intersect public and private roads in urban, rural and forested regions throughout the state.

Plant trees and create riparian corridors that provide shade, nutrient inputs and Large Woody Debris (LWD) to enhance salmon habitat.

The juvenile salmon heading along our shores on their way to the Pacific face an increasingly diverse web of predators, toxins and climate impacts during their time in the open ocean. Studies show that the longer a juvenile salmon take on its journey to the sea – the more rest stops available with food, shelter and shade – the greater chance it will have to make it to the sea and back to its natal stream to spawn.

Whether climate-forced, or the result of shoreline development, the impacts facing Chinook Salmon, specifically, have a direct effect on the health of our Southern Resident Killer Whales. Protecting this national treasure for the next generation is dependent upon lots of people doing lots of little things to “shore up” salmon habitat: upland conditions that favor stability, cool, clean flowing water, functional riparian buffers, pocket estuaries that provide shelter, and cross shore processes that support the salmonid food web.

There are projects in process to usher the salmon safely under the Hood Canal Bridge. There are projects addressing overfishing. In this County, we don’t have the big rivers for the Chinook, but we do have an abundance of shoreline.

And so Mid Sound invites the community to concentrate on the shoreline, and the habitat it can provide to forage fish and to the juvenile out-migrating salmon who need forage fish to grow strong and survive the journey out to sea.

A Changing Tide

Scientific studies have revealed the critical role natural sediment transfer process plays, seasonally, in balancing the elevation of shorelines and maintaining habitat resources. Hard armoring is actually subject to a considerable amount of scour (erosion). Where setbacks allow, wood and vegetation along the shoreline provide a buffer, and critical shade,

without the scour that can harm shoreline habitat.

In the past, Coastal Engineers designed shoreline armoring (bulkheads, groynes) to increase coastal resilience and reduce erosion experienced by landowners who chose to build homes close to the beach.

Today, Coastal Engineers are designing shoreline armor removal projects to increase coastal resilience and reduce erosion experienced by landowners who chose to build homes close to the beach.

In the past, the beach has been viewed as primarily a recreational space. In Washington State, tidelands are considered privately owned by the landowner.

Today, the beach is viewed as both a recreational space and a shared habitat.

While tidelands remain the private recreational property of the landowner in Washington State, local, state & federal dollars are available for the restoration of habitat that supports endangered and threatened species on Puget Sound shorelines.

In the past, installation of hard armoring was the decision of private landowners, working within their private tidelands.

Today, permitting agencies review shoreline armor projects in terms of their impacts; impacts that reach far beyond the local project property owner. Reviews are based on studies related to drift cells, and their role in providing coastal resilience and critical habitat elements upshore and downshore of hard armor projects.

In the past, a build-up of driftwood represents a danger to coastal properties. Storms that bring wood are destructive.

Today, driftwood represents resilience for landowners and habitat for threatened and endangered species.

When a beach is structured, seasonally, with a build-up of Large Woody Debris (LWD),

a self-maintaining & dynamic system is created, providing coastal resilience & invertebrate habitat. This system shifts with the seasons, providing coastal resilience without the negative impacts of hard armoring (i.e. beach narrowing and scour).

What is a Drift Cell?

From our friends at Shore Friendly:

“Your beach is made of sand and gravel from rivers or from other beaches or bluffs. A drift cell is a segment of coastline with one or more sources of sediment, usually including a bluff, that supplies the nearby beaches. Wind and waves cause a cyclical replenishing of beaches, helped along by rainwater that flows over the surface and into the ground and by seasonal freezing and thawing. The process is often gradual. Some sites can have minimal erosion and then experience a dramatic event such as a landslide during a wet winter. Nevertheless, overall erosion rates are low along Puget Sound.

Bluffs are especially vital to replenishing beaches with material—which is why some of these naturally eroding landforms are known as “feeder bluffs.” In the Puget Sound area, feeder bluffs range in height from a few feet to more than 300 feet. As sea levels rise due to climate change, naturally-eroding bluffs will help build up higher beaches.

Drift cells can overlap, but the eroding material usually stays within a discrete zone. Puget Sound has more than 800 drift cells; you can get information about yours by consulting the Washington State Coastal Atlas. When waves hit the shore at an oblique angle, they can move the sediment along in one direction. Some of the sediment is carried into deeper water, and the rest is deposited on a beach, sand spit, or point.”

Hard Armor Removal is Evidence Based, and Goal Driven

Removal of hard amor restores the natural sediment transfer process within the drift cell

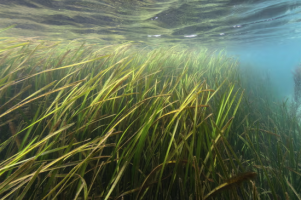

Removal of hard armor also benefits eel grass beds that provide habitat for marine species.

Forage fish are able to spawn near the beach where they are safe from larger marine predators. These forage fish are also able to seek shade and shelter for rest.

Larger populations of forage fish result in healthy orca populations who depend on these fish for survival

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

A keystone species (Chinook Salmon) and a apex predator (Southern Resident Killer Whale) in our Kitsap County waters are critically threatened. Actions that are within human control that will support the health and survival of these species are now supported by federal, state and local grants. Salmon recovery is a priority of the State. Adding to their ecological significance, orcas are classified as an “indicator” species; the health of our Southern Residents represents an indicator of overall ecosystem health and biodiversity.

When a bulkhead is removed, and adjacent property owners have chosen to leave their bulkheads intact, the engineer may be required to design a wingwall on one or both property borders to protect adjacent landowners from erosion & overtopping. Bulkhead and other shoreline removal projects require surveying and permitting. Final designs must respond to permit reviewer comments. The engineer’s stamp on final designs indicates that habitat enhancements are engineered to do no harm to adjacent landowner properties. A Basis of Design report justifies the preferred design alternative from a sustainability, cost, and habitat perspective.

Yes. Elevation surveys conducted seasonally prior to implementation can inform the design, and anticipate the amount of beach narrowing adjacent properties might experience. Seasonal drift will likely balance out the beach over time. Early mitigation may be emplyed by design (like adding sediment to the groyne-adjacent beach at the time of removal). These strategies may present a challenge to the permitting process, but may be justified as a safety element.

No. Engineering and Analysis goes into selecting the least impactful design alternative. This may include leaving a portion of the original armoring, or including a retaining wall in the design to protect project adjacent properties.

A coastal engineer creates a restored beach to slope up to a back beach area area and buffer upland areas during some of the most extreme climate and tidal conditions by design. Vegetation and large woody debris (LWD) are install

The back beach buffer has a planting designed to include vegetation that can be inundated with saltwater, and a palette landward of the beach with decreasingly salt tolerant native plants and trees.

This riparian area plays a number of roles in the restoration. Roots help stabilize the backbeach and prevent erosion. Native plants help filter and slow the infiltration of stormwater. Native plants and trees provide shelter and food for birds and other mammals, as well as polinators important to the habitat. Shade and nutrient inputs are two of the most important functions that vegetation can provide to salmon and the salmonid food web.

If required for the protection of adjacent properties, one or more wing walls might be designed with neighbor input to provide a final project that is both safe and offers the greatest measure of habitat & sustainability.